Joseph Vallone

Although Miwaukee Mafia Boss Pete (G.B) Guardalabene lived on through the 1940s, his handpicked successor Joseph Amato passed away in 1927. Not wishing to step back into the forefront, Guardalabene appointed Joseph Vallone to be the Milwaukee Mafia’s Boss. This move could be seen as solidifying the mob’s two bases: men from Santa Flavia, and men from Prizzi. Until this point, only those from the former had served in the top ranks of the local Mafia.

It was during Vallone’s tenure as boss that the Commission, a governing body of Mafia Families based in New York City, was formed. The criminal council decided that the Milwaukee Family would answer directly to and remain under the influence of the Chicago Outfit.

Vallone’s underboss was Joseph Gumina, who would remain in that role during the subsequent Sam Ferrara and John Alioto regimes.

Sam Ferrara and Joseph Gumina

A capo decina under Vallone was Michele Mineo, who was born in Bagheria on November 29, 1897. He came to America on the SS Belvidere and entered New York City on November 11, 1920. Mineo originally went to meet up with his uncle Filippo Montana in Utica, New York, but then came to Shawano County, Wisconsin and finally settled in Chicago where he was a member of the Joseph Aiello Mafia faction.

Mineo transferred from Chicago to Milwaukee in April 1927 when fighting broke out between Aiello and Capone. He may have gotten out just in time, as during the summer and autumn of 1927, a number of hitmen hired by Aiello to murder Capone were themselves slain. Aiello was killed a few years later, ending the Mafia’s reign in the Windy City.

1932 – Liquor Law Violations

On June 13, 1932, Joseph Vallone (now living at 421 East Buffalo Street) was arrested with a variety of men on charges of conspiracy to violate liquor laws. A total of forty-five suspects were wanted, including at least ten from Milwaukee, for a bootleg ring that allegedly stretched as far as South Dakota. The ring had been operating since 1928 and had a fleet of trucks hauling its illicit cargo, as discovered in records found at a raided realty office in downtown Milwaukee. Their largest distillery, operating in Baraboo, was also destroyed.

Failed county supervisor candidate Angelo Guardalabene, now at 812 East State Street, posted $2000 in bond. So did Brooklyn-born professional fight promoter Albert John Tusa, 36, and Joseph Domanik, 44, of Racine. Domanik, a former tavern owner, was now running Domanik Wholesale Grocery, which was at 1414 Albert Street — near the Masina and Zizzo shootings.

Tusa said to the press, “I can’t understand it. I’ve never been in the racket and never been in any kind of trouble with the federal government. This whole thing is hurting my family and my business.” Vallone claimed that his only connection to the liquor business was that he sold corn sugar, but denied that he knew what the customers used the sugar for.

Following a grand jury hearing, more Milwaukeeans were charged: Tusa’s secretary Marion Jezo, 24, of West Allis, well-dressed “man about town” Jack Phillips, Jack Barber, Ralph West, Peter Piscitello and malt and hops store owner Sam Holzman. Phillips, who had a history of bribing police and drunk driving, quietly arrived at the federal building and posted his $3000 bond. Joseph Pessin, easily Milwaukee’s most notorious bootlegger, was also indicted, but was already serving time in Leavenworth on prior charges.

Thirty of the original suspects were arraigned on Monday, February 6, 1933 in federal court in Madison before Judge Robert G. Bartzell of Indiana. Agents testified that “the syndicate” transported thousands of gallons of alcohol between Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota, including approximately 3000 gallons each month between just Milwaukee and Madison. All those who appeared pleaded not guilty. Some of the defendants, including Ralph West, were still at large. West was considered by some to be the “big shot” or “ring leader” of the whole affair.

The whole situation amounted to very little, as the public’s interest in prosecuting bootleggers waned — Prohibition was on the way out. Most of the defendants, including Vallone and Marion Jezo, ended up having charges dismissed or paid fines that were half their original bond. Tusa paid $1000, while Guardalabene paid $500 and was given eight months probation. Phillips and Pischitello were put on probation for six months. West had some unrelated charges dropped in January 1935, after government witnesses could no longer identify him as the operator of a distillery in Plainview, Minnesota (near Rochester).

1935 – Second Trial

A second liquor conspiracy trial finally began in February 1936, with only two of the Milwaukee defendants from the first trial facing charges: Ralph West and Albert Tusa. The claims were now also reduced to the allegation that various men conspired to ship alcohol across state lines without the proper labels. The alcohol was claimed to be at least 48,000 gallons valued at $250,000 ($4.2 million today). Judge Gunnar H. Nordbye was presiding. Tusa’s involvement was made clear. Driver Victor Thomas testified, “I went to Milwaukee where we met Al Tusa at the Athletic Club, and from there to Sheboygan, where we got the liquor.” He ultimately had the charges dismissed in June 1938.

Jack Phillips was sentenced to ten years in Leavenworth in May 1936 on an unrelated liquor conspiracy charge. His partner in that case was Mitchell Brisson.

1944 – OPA Lawsuit

The only other legal trouble Vallone seemed to have was when he and Pasquale Migliaccio were sued by the Office of Price Administration (OPA) on Friday, September 15, 1944, with the OPA claiming that the grocers were selling their sugar and processed foods for “overceiling” prices. The agency demanded they be fined and asked to be awarded damages of three times the amount overcharged.

This was not at all uncommon, with countless businesses coming under the scrutiny of the government during World War II. (How the case came out is unknown to the author.)

Check out the Milwaukee Mafia Podcast Episode on Milwaukee’s Gambling Empire

Chief Kuchesky and Gambling

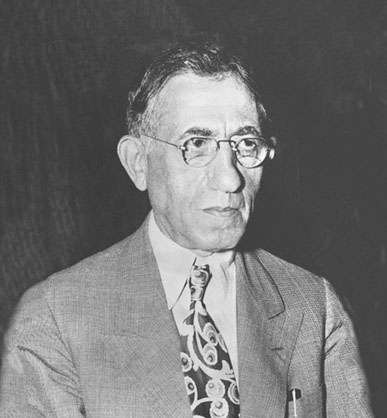

With Prohibition wrapping up and murder becoming more uncommon in the Ward, one crime highlights the years presided over by Vallone: gambling. The criminal underworld’s greatest foe in the 1930s was undoubtedly Police Chief Joseph Kuchesky, who made vice — and particularly gambling — his number one target during his time in office.

Gambling has always been the lifeblood of organized crime in America, and Milwaukee in the 1930s was no exception. The syndicate utilized the services of bookie Louis Abraham Simon, in his downtown office at 231 West Wisconsin Avenue, who gave a significant cut of his profits to the mob in exchange for “protection”. Simon, in turn, used Moses “Moe” Annenberg’s Nation-Wide Wire Service; Annenberg had been sending the results of horse races to gambling houses all over the country, allowing bookmakers to accept wagers right up to the time of the pistol, and helping gamblers collect their payoffs immediately, rather than wait for published results.

Chief Kuchesky

1936 – Pinball Machines

Kuchesky struck out against an unlikely scourge in December 1936 — pinball machines. Along with assistant city attorney Carl Frederick Zeidler, he helped draft an ordinance to outlaw any coin slot machines within city limits that did not dispense merchandise. He told the press, “The pinball machine is one of the worst devices to tempt gambling by young people that has ever invaded our community, and it will have to go.”

Kuchesky had found that machines were earning an average of $150 each on the weekends; his push was backed by the Milwaukee Woman’s Club and the YMCA, who told of a story involving a West Allis boy who stole $30 to feed his pinball addiction.

(Zeidler later became the mayor of Milwaukee at only 32 with the help of speech writer Robert Bloch — the author of “Psycho”. He resigned to serve in World War II on the SS La Salle and died in battle off the coast of South Africa.)

Other proposed ordinances were submitted to counter Kuchesky, including one that kept the machines legal and required the operators to be licensed. Rather than arrest, jail and fine tavern owners, why not have them pass some of the estimated $2,000,000 annual profit on to the city? This alternate view was argued by Alderman Martin Higgins, assistant district attorney George Bowman, and attorney Joseph Padway, counsel for the Pinball Board of Trade.

Padway asserted that as many as 12,000 people depended on the machines for their livelihood and that a ban would do nothing to stop gambling. “You can gamble with the devices,” he conceded, “but you can gamble likewise with playing cards, automobile license plates or on whether the king will marry Mrs. Simpson. If you want to end all gambling, you would have to abolish the king and Wally as well as pinball machines.” Not surprisingly, the common council decided that licensing was more practical than a ban.

1937 – Nuisance Businesses

With gambling convictions tough to secure, Kuchesky changed his angle to injunctions ordering that buildings be closed down as nuisances. In June 1937, for example, with the help of Judge Daniel W. Sullivan, he was able to shut down downtown establishments with such names as the Columbia Club, Eleventh Street Bridge Club, 744 Club and 428 Club. Each had been raided several times in the recent past. The chief also received pushback from people claiming he unfairly targeted some gambling while ignoring others. Brought to his attention were games at church functions where prizes were given out. Kuchesky flatly dismissed the claim that such games of chance were gambling, and said the gamblers “are just trying to confuse the issues by claiming that everything is gambling.”

1938 – Vagrancy Charges

Kuchesky unleashed another great legal tool in October 1938: the ambiguous charge of vagrancy. He stationed members of the vice squad outside known gambling dens in the downtown area and arrested all employees as “jobless”. The chief told the press, “I contend that any employees of a gambling outfit, whether he runs a wheel, handles a race sheet or is a spotter on the sidewalk, is a vagrant under the state law.” The district attorney’s office opposed issuing such warrants, but grudgingly obliged. This had the noticeable effect of scattering the gambling element — bets were now handled by telephone or by runners, and some gambling operations moved their businesses out into the country. One spot on North Plankinton was raided enough times that they moved to the county edge and those who wanted to play craps or roulette took a designated “taxi” found in the former business’ parking lot.

1939 – Annenberg’s Nationwide Wire Service Shuts Down

And then came Chief Kuchesky’s greatest victory. When Annenberg’s Nationwide Wire Service shut down in November 1939, Kuchesky modestly called the closure “a good thing for Milwaukee.” This modest statement failed to take into account his key role in the closure — he had submitted an affidavit to Samuel Klaus, special district attorney in Chicago, saying the firm’s end would help police in their crusade against gambling. “Despite constant and diligent efforts on the part of the Milwaukee police department to suppress gambling in the form of betting or wagering on the results of horse races, it has not succeeded in eradicating this evil,” he wrote. Such easy access to racing results “makes suppression of the evil most difficult and eradication impossible.”

Through pressure on AT&T and Western Union, the lines were cut to Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Iowa in early November, and all twenty-eight of the company’s offices went dark on November 15. The Associated Press reported that horse race gambling instantly dropped anywhere from 25% (Los Angeles) to 90% (Chattanooga) in various markets. San Francisco and Portland allegedly stopped completely. The only city to remain “wide open” was Hot Springs, Arkansas, the home base of English gangster Owney Madden.

Annenberg, originally from Milwaukee, was targeted on tax violations and still had business partners in the city who faced legal trouble at the time of the closure. Russian-born Aaron Trosch, the secretary-treasurer of Milwaukee News Company, was charged with aiding Annenberg in helping him evade taxes. Julius J. Smith, Annenberg’s Milwaukee accountant, was found to have made false statements before a grand jury. Even Louis Simon, an Annenberg customer, was caught in the web, when it was found that he had bribed a grand jury witness to lie on Annenberg’s behalf.

While this by no means ended gambling in Milwaukee or elsewhere, the removal of Annenberg was a serious blow to the bookie profession — results now had to come in by expensive long distance telephone calls or through such unorthodox sources as Cuban radio.

Annenberg ended up pleading guilty to tax evasion and died in prison. His son, Walter, went on to rehabilitate the family name with his extensive philanthropy and creation of media sensations “TV Guide” and “Seventeen”, among others.

Moses Annenberg

The 1948 John Doe Hearings

In July 1948, pressure was put on the police by the Milwaukee Journal to investigate policy wheels in the 6th Ward and allegations that some members of the police department were being paid off by the gamblers there. The newspaper alleged that there were eleven policy wheels in operation, an increase of four over the prior year. They also pointed out the large number of police officers stopping by Smoky’s Smoke Shop. Chief John Walter Polcyn, who replaced Kuchesky in August 1945, responded to this publicly, saying any officer there was “in the line of duty” at the time and while Charles “Smoky” Gooden may have had a record, he was not known to have been involved with policy since 1933.

“Policy”, also known as the numbers racket and various other names, is a low-cost form of gambling where a bettor attempts to pick three digits to match those that will be randomly drawn the following day. Traditionally, the game was started in Italy in the 1500s, but was more common in the United States among the black and Cuban communities. Puerto Ricans played the game in a variation known as bolita, which was quite popular in Tampa.

On July 20, District Attorney William McCauley petitioned Judge Harvey L. Neelen, son of Judge Neelse B. Neelen, for a John Doe investigation into the county’s gambling. Neelen granted the request, and on August 16, the John Doe probe was launched with Judge Neelen serving as a one-man grand jury in a 5th Floor court room in the Safety Building. He was determined to get to the bottom of the black policy racket and any police cooperation with the criminal element in the 6th ward.

Early on, the witnesses seemed to support the Journal’s suspicions. Melvin W. Gerds, a former police officer, testified on August 19 to receiving $85 in “vacation presents” from four black gamblers. He stressed, however, that he provided and promised nothing in return — including police protection. The panel found his answers evasive and he ended up in jail for ten days on charges of contempt. Within weeks, the probe had called thirty-five witnesses and typed up 1,500 pages of testimony

On September 8, Alabama transplant Booker T. Paige told the panel he was having trouble with Thomas Clinton “Joe” Harris and Charles “Smoky” Gooden over rumors that he had allowed photographers to snap pictures through his backyard. Harris and Gooden were the original 6th Ward gamblers, running policy since at least 1929. Harris had several men working for him, including his cousin Willie Sanders Simmons, Tom Morgan, Fred Hearld, Alonzo “Lonnie” Minor, John Edwards and Buster Buchanan. Gooden dropped out when he “went broke” in 1933, but remained strongly connected to the criminal underworld.

On top of Paige’s trouble, the two men had since become enemies and each believed the other “was trying to send him to the penitentiary.” Paige said he had heard Harris had “turned evidence against policy and the police department” and found it strange that Harris “seemed to know everyone who was subpoenaed.” As an example, he said he stopped at Harris’ bar two hours after being subpoenaed and Harris already knew. Paige said Gooden had no policy wheel but Harris had the Delmar and Santa Anita wheels, which were “more on the level than the rest of them.” Despite having no wheel of his own, Gooden took money from others for “protection” that seemed to have little effect in thwarting raids. He did not know who was the head of policy, but had heard it was either Gooden or Cornelius “Big Hand” Ard. Paige said he did not involve himself much with wheels anymore but had once won $900 through the Soldiers Field wheel, operated by the late Burt Trilby.

On September 9, Gust Thornton was called to testify about alleged gifts he made to Gerds. Thornton, a prolific gambler with fourteen related arrests, refused to answer and spent the night in jail. The next day he returned to the stand and remained there forty minutes, smiling as he left the Safety Building. Did he crack? Following him were Thomas Williams, Lonnie Minor and Virgil Hansbrough.

On September 15, Euradell Owsley, 50, testified to working for Joe Harris and helping him write policy. “When Joe told me the heat was coming on this,” she said, “I got afraid and quit. He said [the newspaper] had taken my picture going into Smoky’s.” When asked if Smoky Gooden was the 6th Ward’s policy king she said, “Well, I don’t see how he could be king, so poor he is.” When asked about police payoffs she explained, “I don’t think anybody could have influence with the police, the way they chased us. That’s the reason I let it alone. Sometimes we’d have to run like rabbits to get away, so I don’t see what protection anybody got. They chased all of us.” Owsley later clarified that she thought Harris and not Gooden was the “policy king” as he “has more money and property than anyone.”

On the last day before a recess, September 28, testifying were various 6th ward policy figures: Charles Gooden, Cornelius “Big Hand” Ard, Thomas Morgan (operator of the Phoenix wheel), Joseph Gordon (operator of the Keystone wheel), Fred Hearld (operator of the Top Row wheel), and Shorewood accountant William Ostach. Ard was in the middle of serving a 60-day sentence for running a gambling house. At this point, the probe left the black community behind and spread their net wider to the Jewish gamblers, whose games resulted in much larger bills getting tossed around.

In Maurice Yopack’s John Doe testimony, he conceded he was “a sort of bookkeeper” for Joe Krasno, described as “Milwaukee’s gambling emperor”, for three years. He kept accounts of the gambling business, collected winnings and paid on bets. The pair had four telephones at their 756A North Plankinton Avenue horse betting parlor, and a fifth phone line running directly to Louis Simon that they paid him $82.50 per week for. Yopack claimed to be paid 30% of whatever Krasno’s business earned. Bets typically never ran higher than $100 each, and Yopack claimed to never make any personal wagers. “I don’t do much gambling,” he said. “I’m strictly a family man on the outside.”

On October 22, Louis Simon was called to testify and left two of his books with the panel to examine. His tax returns revealed he had amassed $319,772 in gambling wins during 1948 (over $3 million in today’s money). Although Simon’s service was a great aid to gamblers, the wire was not in itself illegal and he had no fear of sharing at least some of his business transactions. Outside the court room, Simon actually lamented the lack of gambling power in town. “There’s more gambling in cities a third the size of Milwaukee,” he told the Milwaukee Sentinel. “Say all you want, but you don’t see any of the rough stuff here they have in other cities.” He knew what he was talking about. Earlier that year, the FBI put a wiretap on the phone of Chicago mobster Charles Gioe, and found that Gioe’s wife Alberta had spent some time in Miami with Simon. He also knew mobster Frank Fratto, among others.

As of October 24, 175 witnesses had testified with about forty remaining. The court reporters, William Shimeta and Robert Fisher, had already typed up 5,000 pages of testimony amounting to over 1.25 million words. Subpoenas had not yet been issued to Joe Krasno and operator Harry “O’Malley” Glinberg of the Schroeder Hotel, both of whom were in hiding.

On October 27, David C. Kohler’s testimony had him saying he “operated a book upstairs” at his tavern and was paying Louis Simon $57.50 in cash each week to get race results through the Badger News Company. He also had four unlisted telephones. Kohler claimed to have quit booking by the time of the John Doe hearing and was renting that space to one George Fogarty. Kohler listed $45,000 ($435,000 today) of “commissions” on his tax returns for 1945-1947, but refused to say what they were for. Others testifying were Edward Charles “Eddie” Fenzl, mobster Jack Enea, shoe cutter Edward Borgiasz, Garrett Stell of Sailor Ann’s tavern and Max Disterfeld, an employee of Louis Simon.

For October 28, Gaston “Tuts” Goldman testified. Goldman was a well-known bookie who operated out of the Astor Hotel. He received his start as the chauffeur for Robert Lawler in the 1910s, when Lawler ran a gambling operation out of his Norman Cafe on Grand Avenue. Others in court that morning were Abe Katz, Isadore Rosen, Michael Marasco, Oscar Plotkin, Sam Shaiken, Nathan Klein, Dave Collier and Theodore Ivalis, a Greek junk dealer from the 6th Ward. In the afternoon came Sam Schatzman, fruit salesman Max Gindlin, Walter Hutchinson and mob associate Joseph Latona. The latter would later be arrested for running a brothel out of the Wind Blew Inn.

On October 29, Dominic “Lem Sputter” Picciurro, involved with the former Ogden Social Club, testified. The club had operated throughout the 1940s at different locations around Jefferson Street and catered to the Italian community. The various operations were raided nine times and many Italians of the criminal community were arrested, most notably John Triliegi (see chapter 15). Also testifying after Picciurro were Charles Rosen, cigar store owner Hyman “Hymie the Bum” Blaufarb, John Unger and Andrew Horvath, an unemployed Hungarian.

As of October 30, four gamblers were still in hiding: Joe Krasno, Maurice “Chunky” Krasno, Harry Glinberg and Louis Joseph “Ash” Nycek.

Former officer Gerds reappeared on November 4 with attorney Eugene Sullivan to purge himself of contempt charges. This time he said the $85 story was a lie and he only told it to taint the police department. “I was mad at Inspector Hubert E. Dax,” he testified. “I worked hard on the police department in the nine years I was on the police department. I did than i believe the average fellow did that was assigned to certain work… I thought that if I could do anything to make it a little rough for Dax, why, I’d like to.”

Joe Krasno finally surrendered on November 15 and testified before the probe. Krasno took in $131,425 in gambling wins in 1947 and $66,930 the following year. Part of this was paid out to partner Maurice Yopack and brother Maurice, and part was paid back in gambling losses. What secrets, if any, he revealed are unknown.

Probe Effects

The first effects of the probe were felt on December 18, when tax assessments were handed down against the black policy operators for unreported income. George Jackson was the biggest offender, owing $17,000 ($164,000 today), but other big sums included Joe Harris at $6,700 ($65,000 today) and Fred Hearld at $4,200 ($41,000 today). Joseph Gordon, Smoky Gooden, Thomas Morgan and Willie Simmons were also billed.

On January 8, Juge Neelen released a 51-page report with conclusions from the probe, showing that while gambling activity was occurring in the 6th Ward and elsewhere, the police were in no way cooperating with the gamblers or looking the other way. On the contrary, the long list of arrests suggested they were ever-vigilant in targeting this area of vice.

On January 27, 1949, as a result of the John Doe hearing, the Common Council unanimously revoked David Kohler’s license for his tavern at 732 North Water Street and Joe Harris’ license for the 711 Club at 711 West Walnut Street. Attorney Sullivan, on behalf of Kohler, vowed to appeal the decision. While the appeal failed, Kohler found another way around the revocation — he moved his tavern to the northeast suburb of Shorewood. Harris was out of the game, and his son Elbert Earl Harris was raided at home in April and found to be running the Chief wheel with Curtis Allen.

In February, Hyman L. Yopack lost the license to his Avalanche Bar at 1417 West Wells Street when the Common Council decided the tavern was nothing but a front for gambler Maurice Yopack, despite no evidence of gambling at the location. Although Hyman was the operator, Maurice was the majority shareholder. Likewise, Russian-born Nathan Katz lost his license for 756 North Plankinton, a tavern where Joe Krasno’s horse parlor was based. The license was granted instead to Katz’s nephew, Edward Kramsky, after he signed an affidavit saying the license would be revoked again if any evidence of gambling was discovered. Edward Fenzl, operator of Fenzl’s Bar at 625 North 6th Street, was the third man to lose a license.

Nathan Katz’s troubles continued in later years, as he was later nailed for $21,262 ($206,000 today) in unpaid taxes and further fined $750 for failing to register with the IRS as a gambler. When he passed on in December 1965, the Milwaukee Journal celebrated him as “a colorful Milwaukee tavern owner and gambler”. Harry Glinberg was later raided at home in October 1951 and hit for $11,889 ($107,000 today) in back taxes.

Ultimately, the probe lead to little more than revoked licenses and tax liens (albeit some very steep liens). The deep corruption they hoped to uproot was never found; and while some gamblers were hit hard, gambling as a whole was barely even slowed.

As for Melvin Gerds, the man whose false stories started the ball rolling, his life took a downward turn. After leaving Milwaukee he became a private investigator in Florida. In December 1951, he was accused of breaking into a woman’s apartment and attempting to rape her. The jury was hung in May 1952 after deliberating for two hours; a new trial was immediately ordered, and in July Gerds was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison.

The Mafia left largely unscathed during the gambling probe, Joseph Vallone retired from the rackets in 1949 and died of natural causes on March 18, 1952. He left behind his wife Martha and daughter Antonina Frances Vallone, who had married Michael Joseph DeStefano. DeStefano was not known to be involved in Vallone’s world.