Milwaukee

Milwaukee was incorporated into a city on January 31, 1846, combining the prior settlements of Juneautown, Kilbourntown and Walker’s Point for a total population of 15,599. City boundaries were North Avenue on the north, Twenty-Seventh Street on the West, Greenfield Avenue on the south, with Lake Michigan to the east. (More info on Milwaukee’s annexation and consolidation history.)

Originally, there were five wards, and each ward was semi-autonomous; each had three aldermen who could levy taxes and were in charge of street building, sidewalks, sewers, buildings, markets and more. For the purpose of this website, the focus is on the Italians in the Third Ward at the turn of the last century.

Third Ward Irish

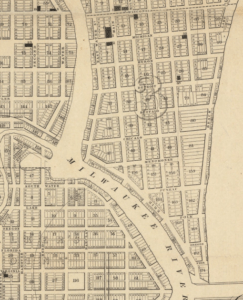

The third ward was located south of Michigan Street between the river and lake, and was occupied by the Irish, a poverty-stricken and socially-marginalized people. Houses covered the east side of the Ward, while factories and warehouses were built along the Milwaukee River.

Milwaukee Third Ward, 1857 (Source and full map)

The ward was full of criminality and was soon dubbed “the Bloody Third” by outsiders. In 1858 alone, 41% of the inmates in Milwaukee County’s jail were Third Ward Irish.

Third Ward Fire – 1892

On October 28, 1892, an oil barrel exploded at Union Oil Company, located at 323 N. Water Street. Within an hour or so of the start of the fire, an explosion in a nearby factory combined with strong winds, significantly increased the fire’s impact. Milwaukee’s warehouse district was ablaze.

The inferno wiped out sixteen square blocks, destroyed 440 buildings (81 brick and 359 wood) including a fire station on Broadway, and 215 freight cars. Miraculously, it only took five lives. Dozens were injured. Almost two thousand people became homeless, and the property loss was estimated at $4.5 to $5 million (in 1892 dollars). Less than 50% of the damage was covered by insurance.

With little left to return to, most of the Irish moved out of the Third Ward to the newly developing Merrill Park neighborhood where they could find work in railway yards.

From Italy to Milwaukee

Around 1895, significant numbers of Sicilians began arriving in the Third Ward in search of better economic prospects. Most came from the province of Palermo, which commonly included Partinico, Termini Imerese, Bagheria, and Santa Flavia (Vito Guardalabene’s home town) . Chain migration created a steady flow of immigrants to Milwaukee. By 1900, the Third Ward population was roughly 6000 people, and was almost exclusively Italian.

Most of these immigrants were unskilled, and took entry-level jobs in the manufacturing and railroad industries. Many men took up a second job, and working conditions were very harsh. According to UWM, in 1915, 75% of Italian immigrants worked manual labor jobs; another 15% worked as tradesmen throughout the city, with the remaining 10% working service jobs such as barkeepers or in small businesses like peddlers or grocers.

Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Church

Catholicism was very important to the vast majority of the Italian immigrants, and they wanted a church that understood their culture and spoke their language. On October 9th, 1904 the cornerstone for the Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Church was placed at 419 N. Jackson Street in Milwaukee. Once complete, the pink exterior brick lead to its famous nickname, “The Little Pink Church.”

The first wedding at the newly-constructed church was the wedding of Salvatore Dentici and Nicoletta Busalacchi on January 17, 1904, with Father Dominic Leone presiding.

Little Pink Church

Father Leone arrived in the United States in 1903, and was prominent in Milwaukee’s Italian community. Historian Mario Carini wrote that Leone “had a dynamic personality, which made him extremely popular with both the immigrants and the city’s non-Italians.” On June 17, 1912, Father Leone’s cousin, Dominic Leone, was murdered. (Both were named after their shared grandfather.)

Leone was an Italian political leader, and had been promoted to superintendent of garbage collection just prior to his death. Leone’s funeral on June 19, 1912 was “one of the largest Italian demonstrations in the city,” lead by pallbearers Angelo Guardalabene and Tony Bellant.

No one was held responsible for Leone’s murder.

The church’s last Mass was on July 30, 1967.